[Because this post relies on images and captions to images, neither of which renders well on smartphones, in my experience, I suggest you view it on a computer or tablet for an optimal experience.]

As I proceed with my work on A Certain Gesture: Evnine’s Batman Meme Project and Its Parerga!, I find myself thinking not infrequently “I wish I had paid more attention as a child.” I am time and again led right up to the edge of my recollection of people, events, and objects that populated my childhood, each carrying so much, not just of their own histories, but of my history. They were messengers from the worlds that made me, messengers that I heeded far too little. Now, as I try to comprehend some of those worlds, I am frequently baffled, their inhabitants hovering just beyond my grasp. I wish I had paid more attention as a child.

When I began writing this post, over two years ago(!), I had a dim sense that many of these isolated fragments, these messengers, some material and others lodged only in my memory, were connected with the world of Russian Jewish émigrés in New York (often via London, Paris, and Berlin). As I have resumed and intensified my work on the post in the last week or so, this suspicion has been confirmed. This post, therefore, is something of a companion piece to this earlier one, which it intersects at one point I will indicate when we get there.

On a wall in my home in Miami , there hangs this wonderful picture:

It was painted by Nina Evnin, the first wife of my father’s uncle, and dated 1947, the year my parents were married. My parents were, in fact, introduced through the joint efforts of Nina and my mother’s mother, Lillian Kruskal Oppenheimer. Nina and Lillian were good friends and had probably become acquainted owing to the business connections between their husbands, Oscar Evnin and Joseph Kruskal, both furriers in New York. After he was demobbed from the British Army in 1946, my father went from London to New York to learn the business from Uncle Oscar and, presciently, Nina and Lillian saw the potential for a match.

Brunya and Oscar were the lucky ones among the children. The two daughters, Julia standing and Raya sitting, died young, possibly both by suicide over unhappy love affairs. Another brother Mordecai (Motty – an Eitingon name), standing next to Brunya, was killed in World War I. The saturnine man on the left was Julia’s husband.

This photo is itself an artifact that pervaded my childhood, no doubt influencing my, and certainly my father’s, conception of what a family is. I will spare the reader the sight of an attempt my immediate family made to produce our own comparable photo in 1973.

Given the date of Nina’s picture and her role in my parent’s marriage, I conjecture that the painting was given to them by her as a wedding gift. It was a fixture of my childhood and when, in 1977, my parents disassembled the home in which I was born and grew up, I took possession of it. I have always loved it.

Ubiquitous through my childhood, too, were Kruskal Furs pencils. My grandmother Lillian must have brought them on her visits to us in London, or perhaps my mother had a vast supply as part of her trousseau! They came in two thicknesses, one fatter and one (pictured) thinner than a standard pencil. (Were those odd sizes themselves standard in some place, at some time? I remember feeling their strangeness in my hand as a child.) Now, fifty years later, this lonely pencil, in the possession of my sister, is the only one I know of still in existence.

Joseph Kruskal arrived in America a four-year-old, impoverished, fatherless boy, from Estonia in 1896. Some of the history of the Kruskal family is told in Two Baltic Families Who Came to America: The Jacobsons and the Kruskals, 1870-1970, by Richard Brown. I remember its author, Dick Brown, coming from the US to visit in the early seventies. “Dick is writing a book”, I would hear. Very likely, he stayed with us. But I never really knew who he was! (His mother was a Kruskal.) As for Joseph Kruskal, before he died in 1949, he made, lost, and remade a fortune with his fur business, Kruskal & Kruskal, Inc., which operated, as the pencil informs us, from 150 W. 30th St from 1932 until 1986 (and before that, from another Manhattan address). You can read a brief account of the business here, under “Kruskal, Malvin & Co., Furs.” And here is an (undated) picture of the W. 30th St. building, with a billboard for my grandfather’s firm. If the firm was there until 1986, surely I must have been taken to visit it on one of our not-infrequent trips to the US? But if so, I have no memory of it.

Some time in my mid-teens, under circumstances that now escape me entirely, I was, for a very brief period (possibly as brief as a single day), close to Nina. She and Oscar had divorced around 1949 or 1950 but, I suppose through her friendship with Lillian, she remained in my immediate family’s orbit. She took me on my first visit to the Guggenheim Museum. I do remember walking down the spiral ramp, stopping to look at pictures, and, filled with awe, hearing her tell me how she knew this painter and had been painted by that one. Alas, I don’t now remember which painters she was talking about. Perhaps, among others, her renowned teacher, Sergey Sudeikin, who painted this very beguiling portrait of her?

Above, I said that the Evnin and Kruskal families must have known each other through their common involvement in the New York fur trade. But there is a particular reason why they should have been on familiar terms. The matriarch in the imposing family photo above was, you may remember, Zissia, née Eitingon. She was, in other words, part of the vast Eitingon clan about whom my distant cousin, Mary-Kay Wilmers, has written a fascinating book, The Eitingons: A Twentieth Century Story (2012). One of the most prominent of the Eitingons was Motty, a second cousin to Zissia (whose eldest son, recall, was Motty too). Motty Eitingon was a towering figure in the international fur business. He was almost certainly exploited by the US government to open unofficial channels with the Soviet Union. And in 1928, Wilmers tells us, his company, Eitingon Schild, which according the New York Times was the “dominant skin dealer of the industry,” acquired Kruskal & Kruskal, Inc., “the largest coat jobber in the fur trade” (NYT quoted in Wilmers, p. 91). So the Evnins and the Kruskals were already connected in New York even before Oscar and Nina arrived there from Paris (where they had gone from Russia).

Other prominent Eitingon relatives of mine, about whom Wilmers writes and who will appear in A Certain Gesture: Evnine’s Batman Meme Project and Its Parerga!, include Max and Leonid. Max Eitingon was a psychoanalyst, a close associate of Freud, and the source of money for much of the early psychoanalytic movement. He was among the founders of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute, which formalized the method of instruction for trainee psychoanalysts (lectures, training analysis, supervision of cases) that still goes by the name of the ‘Eitingon method.’ Leonid (Nachum) Eitingon was a major figure in the NKVD/KGB. It was he, in fact, who organized the assassination of Trotsky, recruiting Ramón Mercader, developing his cover, and waiting around the corner from Trotsky’s compound, ready to whisk Mercader away if the need arose. (It did not; Mercader was apprehended by the police.) Another of his exploits is the stuff of fiction. Around 1943, Leonid trained Nikolai Khokhlov, a Russian vaudeville performer (an “artistic whistler”), over a year and a half, to impersonate a German officer. When he was finally ready, Khokhlov parachuted into Minsk under the name “Lieutenant Otto Witgenstein” and successfully completed his mission of blowing up Wilhelm Kube, the “Butcher of Belorussia” (Wilmers, pp. 340-1).

Motty Eitingon, with his great wealth, was a patron to many artists, especially musicians. One passage about this in Wilmers’ book especially caught my attention:

In October 1927… when it was announced that the young violinist Benno Rabinof would shortly make his debut at Carnegie Hall, the New York Times reported that for many years the boy from the East Side ‘with a hunger for music’ had been looked after by a guardian angel in the form of ‘Motti Eitingon, a New York merchant, who was so convinced of his future that he took the financial cares off the family’s shoulders.’ … On occasions like this it’s not hard to see — or rather it’s hard not to see — Motty as a money man with a soft heart in the old Hollywood mode. (p. 210-1)

When I read this passage, I remembered another object from my youth, an LP that, at least for a certain period of time, I listened to a lot:

In my mid to late teens, I thought I was going to be a composer. Around 1975 or 1976, just after the death of Benno Rabinof, I went to visit Sylvia Rabinof, his widow, accompanist, and a very prominent musician in her own right, in New York. The visit must have been arranged through the good offices either of Lillian or Nina (was this on the same visit during which Nina took me to the Guggenheim?), one or both of whom must have been friendly with the Rabinofs. Sylvia was nice but did not think much, I understood, of those of my compositions that I showed her. (I had a similarly discouraging experience around that time in London, with the composer Joseph Horovitz, though I don’t remember which mutual friend facilitated the meeting.)

Although Benno and Sylvia did not record much — they preferred live performance and teaching — it seems they were quite significant. Benno studied with the great violinist and teacher Leopold Auer. (Perhaps Motty Eitingon payed for these lessons.) Auer’s other students included David and Jascha Heifitz and Efrem Zimbalist. Zimbalist was another Russian Jewish émigré whose son, Efrem Zimbalist Jr., was the star of The F.B.I., a television show from the mid-60s whose opening (“A QM [Quinn Martin] production, starring Efrem Zimbalist Jr.”) has stayed in my mind for over 50 years. (Efrem Zimbalist Jr., by the way, played Alfred Pennyworth, the Wayne family old retainer, in the animated Batman series from the 60s. In another post, I made a surprising discovery about the actor, Alan Napier, who played Alfred in the live action series from that time!)

Another student of Auer’s was yet another Russian Jewish émigrée, Clara Rockmore (née Reisenberg). Rockmore was forced to give up the violin owing to tendinitis but struck up a connection with another Russian then living in the United States, Léon Theremin, inventor of the theremin, and so became the first player to bring a high level of artistry to the newly invented instrument. (Theremin proposed to her but she declined.) Here she is playing Saint-Saëns’ The Swan. If you’ve never seen a theremin played, it’s worth a look.

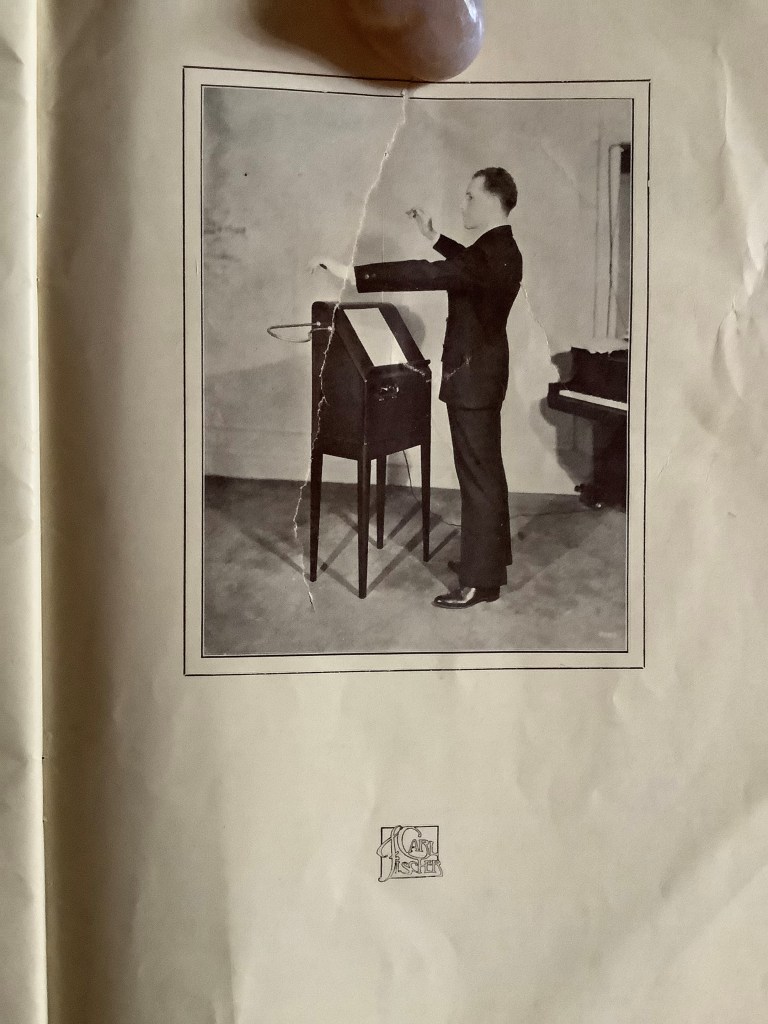

As I was writing this, I suddenly recalled that my grandmother, Lillian, herself owned a theremin! In fact, I have now convinced myself that I remember trying it out at a young age, though I suspect this is not a genuine memory. Whether or not I did, when I was old enough to care, Lillian no longer owned it. Surely she, and Nina, must have known Theremin and Rockmore. Perhaps, like Rockmore, her theremin was even given to her by its inventor. While I don’t have Lillian’s theremin, I do have, still in my possession, a book that probably belonged to my mother in the 1930s and 40s (she was a clarinetist of no mean accomplishment) that explains all the different musical instruments. It was invaluable to me in my own attempts at composition, giving the ranges of the different instruments, the clefs their parts are written in, and so on. It also had, for each instrument, a picture of someone playing it. Even as a teenager, I found the old-fashioned quality of these pictures remarkable. Truly up to the minute, the book includes the theremin.

What, I imagine you asking, does all this – interesting as it may be – have to do with A Certain Gesture: Evnine’s Batman Meme Project and Its Parerga!? Let me tell you. It has precisely three things to do with it. First, some of the people I discuss here will appear in the book. Secondly, the post itself functions as a kind of personal “cabinet of curiosities,” and the cabinet of curiosities, the Wunderkammer, is one of the forms under which I conceive of my book as a whole. But the third connection is the most significant.

I hope it is evident that my fascination with the image of Batman slapping Robin is fueled by real psychological sources. Among them is the fact that, as a young boy of around seven, I participated in the making of some films by my older brother and his friends (who were around 16 years old). I had, not long before these films were made, been given, as a birthday present, a Batman mask, cape, and vambraces. (I mention this in an interview I gave about my book in which I incorrectly call the vambraces ‘grieves.’) Perhaps because of the presence of this gift, or my evident enthusiasm for Batman, my brother and his friends incorporated a scene into their film in which Batman and Robin appear. Although the Batman gear was mine, and although it was, evidently, comically small on these 16 year olds, I was only allowed to play Robin in the scene while one of the friends played Batman. I will discuss this scene at much greater length in the course of my book – there are depths to the significance of that episode for my current book that I am not even hinting at here. But here is one still from the film. And as you can see, Nina’s painting hangs on the wall behind Batman’s head!

Simon, what wonderful images, thank you for sharing, un abrazo, John

LikeLike