Next week, I am going to teach again David Kaplan‘s wonderful paper “Dthat.” David was one of my teachers in graduate school and although I did not work especially closely with him, I had enough experience of him to be smitten. He had, and no doubt still has, a luminous and humorous intelligence that was utterly beguiling, both personally and intellectually.

It’s a bit hard to explain what “dthat” is to those not immersed in analytic philosophy of language but I’ll give it a try. Kaplan, in the paper of that name, is discussing the semantics of the English demonstrative “that” and makes certain conjectures about how it might be used. Rather than argue over the substantive question of whether the English expression is used in the conjectured way, Kaplan employs a technique not uncommon in analytic philosophy (another instance of which I touch on in my post Shmidentity Politics) and introduces a neologism about which he can stipulate the features that are merely conjectured to apply in the real-life case. “Dthat,” (pronounced exactly like “that”) is a demonstrative device about which roughly the following is stipulated: when it appears in a sentence, what it contributes to the meaning of an utterance of the sentence is nothing other than the object demonstrated. This extends to its use when coupled with descriptive content. So in an utterance of “Dthat slap you just gave me really hurt,” the meaning of the expression “[the] slap you just gave me” does not enter into the meaning expressed by the utterance, but functions in something like the way pointing does, if I point to an ice sculpture and say “Dthat is going to melt pretty soon.” The pointing is, we might say, a parergon to the meaning of the utterance; and just so is the meaning of “[the] slap you just gave me” a kind of linguistic parergon – a paratext – to the meaning of the utterance in question.

A long-standing question for philosophers of language is whether proper names function, semantically, in a way similar to “dthat.” Proper names, Kaplan says, are a “theoretician’s nightmare.” He concludes that “if it weren’t for the problem of how to get the kids to come in for dinner, I’d be inclined to just junk them.” Perhaps because his character is so evident in this sentence, it’s always been one my favorite bits of philosophy! Of course, unsurprisingly, there is a very deep point there too. Names are used not only to refer, which is how almost all philosophers of language approach them, but to address as well, to interpellate (as Althusser puts it). It is, Kaplan suggests, their use as means of interpellation that makes it impossible to get by without proper names.

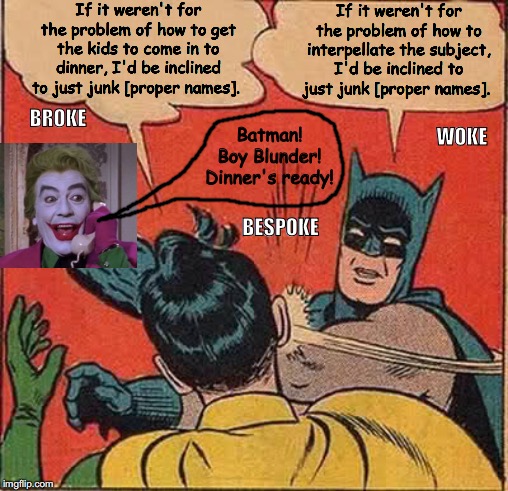

This is the background to a meme, composed several years after most of the others that will appear in my book, that will be the final entry in A Certain Gesture: Evnine’s Batman Meme Project and Its Parerga!. In it, I combine the form of the Batman-slapping-Robin meme with that of another meme: Broke-Woke-Bespoke. This allows for some allegedly tired content (though I hope this post makes evident how inappropriate I think it is to regard Kaplan’s original formulation as in any way tired!) to be transformed into a ‘woke’ version, and ultimately into a ‘bespoke’ version, the acme of its possible expressions.