In my previous post on this blog I mentioned that I had just finished the commentary on a Batman meme that was in Yiddish. I had sought a lot of help in writing this commentary since, not to put too fine a point on it, I often didn’t know what I was talking about. Among those to whom I turned was a very distinguished but somewhat irascible expert on Yiddish. (Do I give away his identity, to those in the know, if I say that he prefers to call that language “Yidish”?)

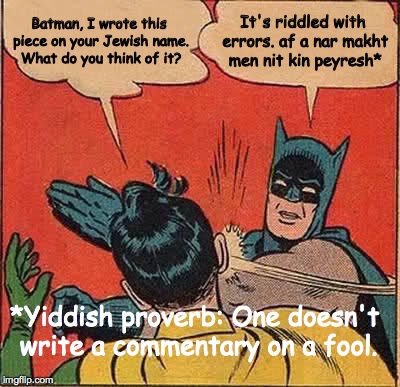

I sent him the completed draft of the commentary, 8,000-9,000 words long, and, with amazing generosity, he read it all! In it, I briefly mentioned the role Google Translate played in my quest to obtain the Yiddish text for the meme. I summarize this expert’s response to my commentary using a Yiddish proverb he himself used in reference to Google Translate’s Yiddish:

I can only hope, on the basis of his kind offer to help me improve my text, that he does not think me too much of a fool! (But note, for future reference, the small “a” at the beginning of “af a nar.”)

One issue that he raised was my Romanization of the name <Simcha Bunim>. (Of course, to explain the issue, I have already to implicate myself here. I will use pointed brackets to indicate reference to a name that is independent of the alphabet or orthographic system by means of which I achieve that reference). <Simcha>, he explained, can be either a Hebrew or a Yiddish name. <Bunim>, by contrast, can be only a Yiddish name. (It may derive from the French “bon nom” or “bon homme,” by the way.) Therefore, he reasoned, the compound name <Simcha Bunim> can only be a Yiddish name. Therefore the correct Romanization (there are various methods, but he either alludes to a consensus or the scheme he considers the best) must be “simkhe-bunim,” not, as I had it, “Simcha Bunim.” No capitals, hyphen, and “khe” not “cha.” (af a nar makht men nit kin peyresh!)

Clearly his reasoning depends on some substantive principles:

- That a name is in a language. While this seems right for examples like “Venezia” and “Venice,” the Italian and English names of the same city, it is at least not obviously true for all names. (Kripke discusses this in “A Puzzle About Belief.” I must remind myself of what he says.)

- That a single name can be in more than one language. (But perhaps this assumption is not actually necessary for his reasoning.)

- Most importantly, and most controversially, that if, in a compound name A-B, A can be in languages L1 and L2 and B can only be in L1, then the compound must be in L1. Even if this is right, it does not uncontroversially describe the situation we are examining. It might be, for example, that when A and B compound, B enters all the languages that A is in. Furthermore, we are still left having to deal with cases where A is in L1 only and B is in L2 only; in what language, then, is the compound name A-B? Whatever we say will give us a possible move to make in the case where A is in L1 and L2 but B only in L1.

Well, I have no idea how to resolve these issues. But return to my helpful critic’s preference for “Yidish” as the name of the language at issue. In what language is the name “Yidish”? The Romanization of the relevant Yiddish word will be “yidish,” with a single “d” and no capital. But “Yidish” has a capital and so cannot be a well-formed (i.e. well-spelled and Romanized) Yiddish word. And it cannot be English either, since the English name for Yiddish, well-established by convention, is “Yiddish”!

Perhaps I’ve never seen his name actually written, only passed down orally, but my great-grandfather was Simcha Superfine. It never occurred to me to write his name “Simkhe”, let alone “simkhe”. But maybe there’s a difference between the common noun “simkhe” for joy and the proper noun “Simcha” as a man’s name. And if we’re going to be purist in the way your expert wants, then wouldn’t we have to spell my great-grandfather’s name “Simkhe Zuperfayn”? But the truth is – despite Livak striving for order and purity in this world – that languages are always mixing and being mixed up. What can one do? After all, af a nar, makht men nit kin peyresh. Nu?

LikeLike

RLA, indeed, languages are always mixing and being mixed up. And common practice will probably find 20 different ways of spelling that one name! But in scholarly contexts, at least, consistency is usually desirable. As I am finding out in this case, the difficulty is in determining what really is a scholarly context and what isn’t!

LikeLike

RLA, I should have said that your great-grandfather’s name was Hebrew and not Yiddish, and hence it is fine to go on writing it as “Simcha”! 🙂

LikeLike

Yes, I thought of that, too. Was that usual? I’ll ask a friend of mine, who would know about these things.

LikeLike

Please report back!

LikeLike